Concurrency 2: Concurrently Readable Structures

In this post, I'll discuss concurrently readable datastructures that exist, and ideas for future structures. Please note, this post is an inprogress design, and may be altered in the future.

Before you start, make sure you have read part 1

Concurrent Cell

The simplest form of concurrently readable structure is a concurrent cell. This is equivalent to a read-write lock, but has concurrently readable properties instead. The key mechanism to enable this is that when the writer begins, it clones the data before writing it. We trade more memory usage for a gain in concurrency.

To see an implementation, see my rust crate, concread

Concurrent Tree

The concurrent cell is good for small data, but a larger structure - like a tree - may take too long to clone on each write. A good estimate is that if your data in the cell is larger than about 512 bytes, you likely want a concurrent tree instead.

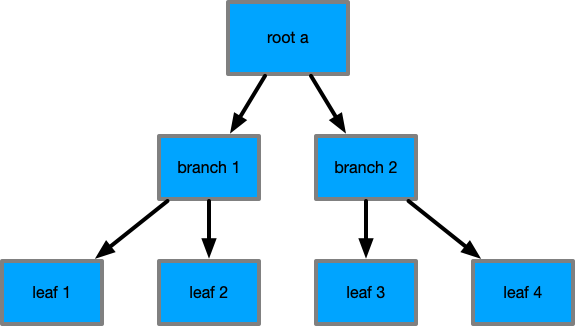

In a concurrent tree, only the branches involved in the operation are cloned. Imagine the following tree:

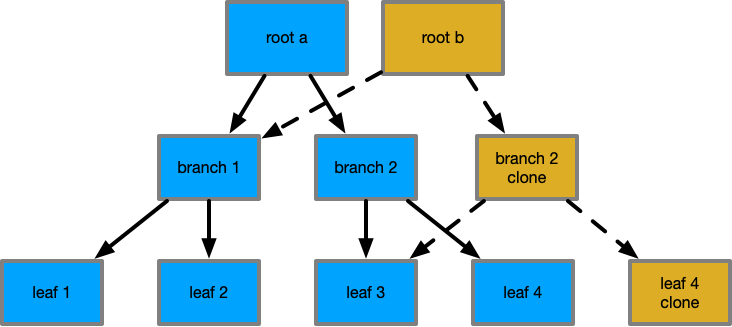

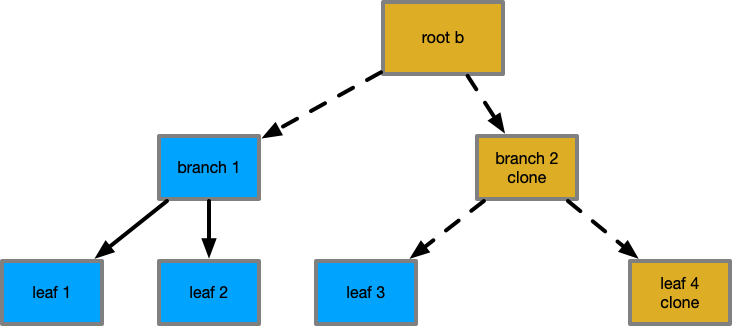

When we attempt to change a value in the 4th leaf we copy it before we begin, and all it's parents to update their pointers.

In the process the pointers from the new root b to branch 1 are maintained. The new second branch also maintains a pointer to the original 3rd leaf.

This means that in this example only 3/7 nodes are copied, saving a lot of cloning. As your tree grows this saves a lot of work. Consider a tree with node-widths of 7 pointers and at height level 5. Assuming perfect layout, you only need to clone 5/~16000 nodes. A huge saving in memory copy!

The interesting part is a reader of root a, also is unaffected by the changes to root b - the tree from root a hasn't been changed, as all it's pointers and nodes are still valid.

When all readers of root a end, we clean up all the nodes it pointed to that no longer are needed by root b (this can be done with atomic reference counting, or garbage lists in transactions).

It is through this copy-on-write (also called multi view concurrency control) that we achieve concurrent readability in the tree.

This is really excellent for databases where you have in memory structures that work in parallel to the database transactions. In kanidm an example is the in-memory schema that is used at run time but loaded from the database. They require transactional behaviours to match the database, and ACID properties so that readers of a past transaction have the "matched" schema in memory.

Concurrent Cache (Updated 2020-05-13)

A design that I have thought about for a long time has finally come to reality. This is a concurrently readable transactional cache. One writer, multiple readers with consistent views of the data. Additionally due to the transactioal nature, rollbacks and commits are fulled supported.

For a more formal version of this design, please see my concurrent ARC draft paper.

This scheme should work with any cache type - LRU, LRU2Q, LFU. I have used ARC.

ARC was popularised by ZFS - ARC is not specific to ZFS, it's a strategy for cache replacement, despite the comment association between the two.

ARC is a pair of LRU's with a set of ghost lists and a weighting factor. When an entry is "missed" it's inserted to the "recent" LRU. When it's accessed from the LRU a second time, it moves to the "frequent" LRU.

When entries are evicted from their sets they are added to the ghost list. When a cache miss occurs, the ghost list is consulted. If the entry "would have been" in the "recent" LRU, but was not, the "recent" LRU grows and the "frequent" LRU shrinks. If the item "would have been" in the "frequent" LRU but was not, the "frequent" LRU is expanded, and the "recent" LRU shrunk.

This causes ARC to be self tuning to your workload, as well as balancing "high frequency" and "high locality" operations. It's also resistant to many cache invalidation or busting patterns that can occur in other algorithms.

A major problem though is ARC is not designed for concurrency - LRU's rely on double linked lists which is very much something that only a single thread can modify safely due to the number of pointers that are not aligned in a single cache line, prevent atomic changes.

How to make ARC concurrent

To make this concurrent, I think it's important to specify the goals.

- Readers must always have a correct "point in time" view of the cache and its data

- Readers must be able to trigger cache inclusions

- Readers must be able to track cache hits accurately

- Readers are isolated from all other readers and writer actions

- Writers must always have a correct "point in time" view

- Writers must be able to rollback changes without penalty

- Writers must be able to trigger cache inclusions

- Writers must be able to track cache hits accurately

- Writers are isolated from all readers

- The cache must maintain correct temporal ordering of items in the cache

- The cache must properly update hit and inclusions based on readers and writers

- The cache must provide ARC semantics for management of items

- The cache must be concurrently readable and transactional

- The overhead compared to single thread ARC is minimal

There are a lot of places to draw inspiration from, and I don't think I can list - or remember them all.

My current design uses a per-thread reader cache to allow inclusions, with a channel to asynchronously include and track hits to the write thread. The writer also maintains a local cache of items including markers of removed items. When the writer commits, the channel is drained to a time point T, and actions on the ARC taken.

This means the LRU's are maintained only in a single write thread, but the readers changes are able to influence the caching decisions.

To maintain consistency, and extra set is added which is the haunted set, so that a key that has existed at some point can be tracked to identify it's point in time of eviction and last update so that stale data can never be included by accident.

Limitations and Concerns

Cache missing is very expensive - multiple threads may load the value, the readers must queue the value, and the writer must then act on the queue. Sizing the cache to be large enough is critically important as eviction/missing will have a higher penalty than normal. Optimally the cache will be "as large or larger" than the working set.

But with a concurrent ARC we now have a cache where each reader thread has a thread local cache and the writer is communicated to by channels. This may make the cache's memory limit baloon to a high amount over a normal cache. To help, an algorithm was developed based on expect cache behaviour for misses and communication to help size the caches of readers and writers.

Conclusion

This is a snapshot of some concurrently readable datastructures, and how they are implemented and useful in your projects. Using them in Kanidm we have already seen excellent performance and scaling of the server, with very little effort for tuning. We plan to adapt these for use in 389 Directory Server too. Stay tuned!